Cloudflare regex debacle

A Cloudflare global outage occurred on July 2, 2019 due to a regex that spiked CPU usage on a key component in their service. This regex behavior is sometimes called catastrophic backtracking, and can happen with backtracking regex libraries. Only a few implementations are smart enough to avoid this behavior. In this post, we look at RPL as a regex alternative. If the problematic regex that Cloudflare used had been developed in RPL, it would have produced a linear time solution.

Global outage

The initial announcement by Cloudflare says, “The intent of these new rules was to improve the blocking of inline JavaScript that is used in attacks.”

A subsequent Cloudflare blog entry explains how the regex implementation goes wrong when processing this expression. In this post, we look at how using RPL avoids this problem entirely.

First, some observations about regex in general:

- Regex are hard to read, so we have to break them into pieces to see what they do. It would help a great deal if we had examples of strings that the pattern should match, and strings it should reject.

- It appears that regex found in public GitHub projects are severely under-tested. (A colleague estimates that only 17% are covered at all by automated tests, and the vast majority of those contain only positive tests.) Test cases may not reveal performance issues, but they illustrate what the regex is meant to do, and that can suggest opportunities to refactor.

- Excessive backtracking is easy to trigger accidentally with regex, as happened to Cloudflare in this case.

We make the following claims based on the design of RPL:

- RPL is easier to read, in part because it can be written in composable pieces.

- The Rosie implementation supports executable unit tests, which serve as regression tests and also an important form of documentation.

- Basic RPL expressions (defined below) are matched in guaranteed linear time. (Expressions using look-around run in worst-case polynomial time, and recursive grammars in worse-case exponential time in the size of the input text.)

A proof of the worst-case asymptotic complexity bounds is being written for

publication, but a sketch of the key parts is below. It is straightforward, and

relies on the fact that RPL expressions (like other Parsing Expression Grammars)

are greedy and possessive. Expressions like .* and a? do not backtrack.

First, we look at the Cloudflare regex, and explore how it might have been written in RPL.

An RPL version of the Cloudflare regex

As reported, this is the troublesome regex:

(?:(?:\"|'|\]|\}|\\|\d|(?:nan|infinity|true|false|null|undefined|symbol|math)|\`|\-|\+)+[)]*;?((?:\s|-|~|!|{}|\|\||\+)*.*(?:.*=.*)))

Let’s reformat this expression for exposition purposes, so we can look at what each segment of this expression does. We’ll rewrite it in RPL as we go.

1 (?:

2 (?:

3 \"|'|\]|\}|\\|\d|

4 (?:

5 nan|infinity|true|false|null|undefined|symbol|math

6 )|

7 \`|\-|\+

8 )+

9 [)]*;?

10 (

11 (?:

12 \s|-|~|!|{}|\|\||\+

13 )*

14 .*

15 (?:

16 .*=.*

17 )

18 )

19 )

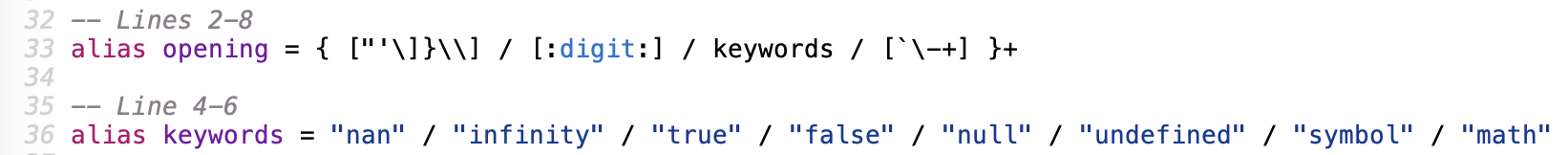

The first interesting segment is on lines 3–7, which contain a set of

alternatives. Line 3 is mostly single characters, all of which have to be

escaped, and then \d which matches a single digit. Lines 4–6 are a set of

keywords, and line 7 is a few more miscellaneous characters.

Lines 2 and 8 wrap up the set of alternatives in lines 3–7 into a non-capturing

group that must appear one or more times, due to the + on line 8.

In RPL, every definition names a capturing group, unless it is an alias, so

that is what we’ll use here for the “open sequence” of input that is matched by

lines 2–8:

Line 9 of the regex matches any number of closing parentheses, optionally followed by a semicolon:

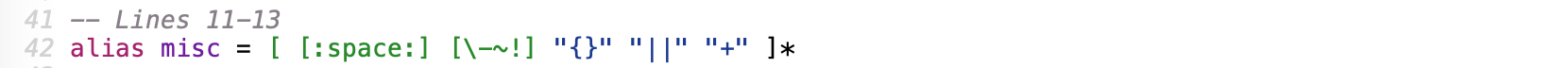

We will return to lines 10 and 18, which delimit a capture group. Inside that capture group are three items:

- lines 11-13 match any number of: whitespace, dashes, tildes, bangs,

{},||, and plus signs; - line 14 matches any number of characters

- line 16 matches any character sequence containing an equal sign,

=

This is a good time to point out that misc is a poor name for a pattern, and

opening and closing are no better. But we don’t know what the regex author

had in mind here. Without sub-pattern names and unit tests for the regex, we

can’t easily know why it was written this way.

We chose the name identifier for the sub-pattern that matches the text before

the equal sign, as this seems like a good guess. In other words, we are

inferring from the regex that the author wants to capture the identifier being

defined. (Otherwise, why have a capture at all?)

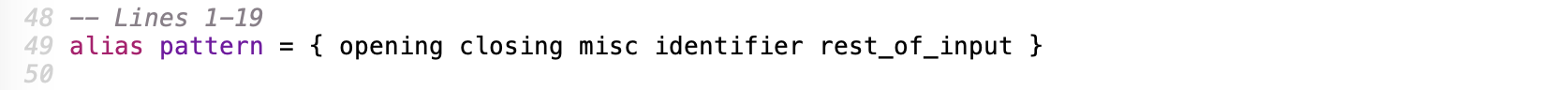

Finally, we can wrap it all together into a single non-capturing pattern that

represents lines 1-19 of the regex (which we named pattern because we can’t

tell what a good name would be):

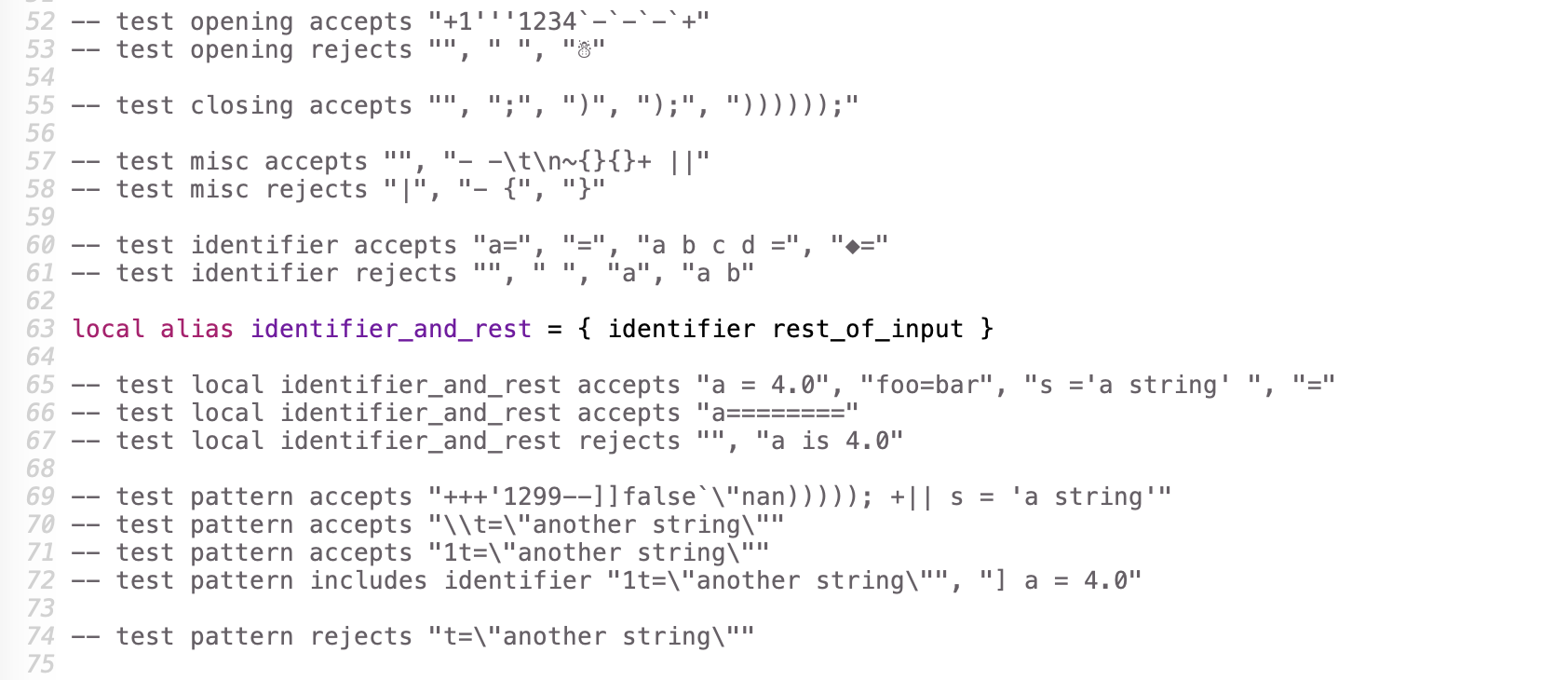

What we have not shown so far is that as we rewrote each segment of the regex in

RPL, we also wrote a few unit tests. While testing, we decided to add a pattern

just for testing (the local pattern identifier_and_rest).

Regarding the test strings: Double quotes must be escaped; common sequences for whitespace characters like \n are recognized; and Unicode characters (in UTF-8) may be present literally or via Unicode escape syntax.

Note: It is not clear from the Cloudflare blogs whether the regex is being used in a mode in which the dot matches any UTF-8 encoded character. By default, Rosie defines dot to match any UTF-8 character, or failing that, a single byte. To change what dot matches, you redefine it locally. There are no global flags that affect the meaning of RPL expressions; semantics are derivable purely from the RPL itself. This is not a small point. It is what allows RPL to be statically analyzed in a meaningful way.

The Rosie implementation executes unit tests with the rosie test command:

$ rosie test code/cloudflare.rpl

code/cloudflare.rpl

All 35 tests passed

$

The complete RPL file is here. It requires the latest Rosie version to run all of its tests.

The definition of pattern we created based on the Cloudflare regex is a

non-recursive RPL expression that we claim will run in worst-case linear time in

the size of the input data. Let’s look at the worst-case time complexity for

increasingly larger sets of RPL patterns.

Worst-case bounds

Important note: Backreferences were recently added as an experimental feature in RPL. The effect of adding this language feature is not included in the complexity analysis.

Basic RPL patterns

Basic RPL patterns include the following “atomic” elements:

- Literal strings, like

"num"and"false" - Character lists and ranges, like

[\-~!](where the dash is escaped) and[a-z] - Named character sets with Posix ASCII-only definitions, like

[:digit:] - The complements of character lists, ranges, and named sets

Basic RPL patterns are closed under composition using the following operators:

- Sequence: if

AandBare basic, so is{A B} - Choice: if

AandBare basic, so isA / B - Choice using character set syntax: if

AandBare basic, andAis a character list, range, or named set, then so is[A B] - Repetition: if

Ais basic, so areA*,A+,A?, andA{n,m}

Note 1: We use the non-tokenized sequence construct

{A B}here. By contrast, the meaning ofA Bwithout enclosing curly braces is:Afollowed by a token boundary (similar in concept to\bin regex), followed byB.Note 2: In RPL,

A*is a valid RPL expression if and only ifAconsumes at least one character. Consequently, these expressions are not valid:A**,A+*,A?*.

Basic RPL expressions are worst-case linear

The atomic elements, by inspection, take constant time when measured against the size of the input. (Clearly, the size of the constant can vary with, e.g. the length of a literal string being matched.)

The Kleene star repetition, as in A*, is greedy and possessive. That is, it

consumes as much input as possible, and after being matched, is never

re-evaluated (so no backtracking occurs).

Since any expression A* is the repetition of a pattern that consumes at

least one character, the most time that A* can take when A is a basic

pattern is when A* consumes the entire input, i.e. linear time.

We state here without formal proof that basic RPL expressions are closed under the operations listed above. To convince yourself of this, you will need to know the following equalities:

A+=={A A*}A?==A / ""(in other words,Aor the empty string)A{n,m}== n copies ofAin sequence with m copies ofA?

Non-recursive RPL patterns

If we add look-around operators to the basic patterns, we get the set of non-recursive RPL patterns:

- Look-around: if

Ais non-recursive, then>A,<A,!A, and!<Aare also non-recursive RPL expressions.

A common idiom in both regex and RPL is an expression that “skips ahead” by

consuming as many characters as needed in order to match another pattern. In

regex, this is typically written .*T where T is some target pattern. In

RPL, .* is greedy and possessive, so we cannot use the same expression, which

will never succeed (unless T is $) because .* will consume all available

input.

A faithful formal conversion of the regex .*T into RPL produces a recursive

pattern that backtracks just as the regex does. But it is often the case that

.*T is written without backtracking in mind. That is, when a regex user

writes .*T, they often mean skip as many characters as needed until the

pattern T matches.

This is easy (and non-recursive) in RPL. Without using any macros, we would write:

{ {!T .}* T }

The meaning is: when not looking at pattern T, match a character, doing this 0

or more times; then match T. This expression will consume input up to and

including the first occurrence of T. It will fail if the end of input is

reached without seeing T.

Because this idiomatic RPL expression requires that we repeat the expression we

are looking for, i.e. T, there is a macro called find that expands to an

equivalent expression. Macros in RPL are applied with a colon syntax, so the

expression above may be written:

find:T

An expression of this form is worst-case linear when T is a basic RPL

pattern.

In RPL, recursive expressions must be written using grammar keyword. Viewed

as another operator, grammar is not in the non-recursive subset of RPL.

Non-recursive RPL patterns are worst-case polynomial

We claim that the worst case complexity for non-recursive RPL expressions is polynomial: the worst case complexity to process an input of length n is O(n^k) where k is the star height of the RPL expression. Star height is defined for regular expressions, but the translation to RPL is straightforward.

A proof suitable for publication is forthcoming.

Where the Cloudflare regex went wrong

The Cloudflare team already identified that the critical part of the regex is

.*(?:.*=.*) (lines 14–16). Two things could go wrong here, and one of them

actually did.

- As observed by the Cloudflare team, there are two instances of

.*in sequence: the one before the non-capturing group, and the one immediately inside it, before the equal sign. Both instances of.*can backtrack. - Also, the expression

.*=.*can be quite inefficient, although it is a common regex idiom.

RPL does not let you write expressions like these, and we will explain why. This may seem to be a limitation, but in fact any formal regular expression is expressible in RPL. And many real-world regex are amenable to automatic conversion to RPL. (An implementation of such a converter is underway. Please get in touch for details.

Since RPL expressions are possessive, any occurrence of .* will consume the

rest of the input. It makes no sense to write the sequence {.* x} for any x

except the end of input marker, $. (An experimental linter has been

implemented which detects exactly this situation, among others. We plan to

build out the linter into a production quality tool.)

RPL users can use [tests to drive pattern development]({% post_url

2019-07-01-PragPub-Article %}), so even without a linter,

an RPL writer will not write .* in the middle of a sequence. If you do, you

will quickly see via your unit tests that nothing after .* will match.

This brings us to the second item, .*=.*, which matches any string of

characters containing an equal sign. If there is more than one equal sign in

the input (and if there are more things to match after this expression), then

more backtracking will occur. Is it important, in this use case, to match

strings with only one equal sign?

It appears not, because as written, the regex will accept many equal signs. And so will the RPL that we wrote to match the regex. See the unit test on line 70.

Does it matter, when there are many equal signs, which one is matched by the

regex .*=.*? Based on how it was written, no.

Given the lack of specificity here, it is easy to convert the expression .*=.*

into RPL. We want to find an equal sign, and then consume the rest of the

input.

Instead of catastrophic backtracking, the resulting RPL pattern does no backtracking. It runs in linear time.

Conclusion

The problematic Cloudflare regex, if converted mechanically to a Parsing Expression Grammar using published methods produces a recursive grammar. Recursive grammars can consume exponential time in a backtracking PEG implementation, just as the original Cloudflare regex can consume exponential time in a backtracking regex implementation.

But in RPL, recursive grammars must be declared with the grammar keyword,

making it plain that recursion is afoot. Any regex that converts to a recursive

PEG, by automated conversion or by hand, might require exponential time to

execute.

This is a property of the structure of regular expressions. However, it seems likely that most regex authors do not intend to write exponential time expressions. In other words, we suspect it is rare to have a regex use case for which an exponential number of cases must be tested.

That is why, when we converted the Cloudflare regex to RPL in this post, we did not do a faithful, mechanical transformation. A faithful transformation would have preserved the undesirable and unneeded behavior!

Cloudflare can avoid the excessive CPU usage caused by their backtracking regex implementation by rewriting the expression. To avoid the problem in the future, they could switch to one of the handful of regex implementations that do not backtrack, like Google’s RE2 or Intel’s Hyperscan.

Changing regex implementations can be fraught, though, because of variations in behavior between them. In particularly awkward cases, a regex moved to a new implementation will appear to work, only to eventually fail in production on some edge case.

Soapbox

In the long run, as an industry, do we want to continue developing production code on top of regex? They are generally hard to read and maintain. There are few practical testing solutions, and run-time exceptions are not uncommon.

These are the primary reasons we developed RPL. The Rosie implementation lets us define patterns in a maintainable way, and package them for sharing. At build time, RPL patterns can be compiled and tested, thus avoiding most run-time errors. Static analysis can alert us to super-linear and exponential worst-case performance during pattern development, as part of “linting for performance”.

Rosie/RPL workflow

The workflow we envision for RPL users is a software development workflow (which is actually quite unlike how regex are handled). RPL diffs like a programming language, making it friendly with tools like git and plain old diff. The Rosie implementation contains an interactive REPL and a trace capability, to aid in debugging.

Most importantly, packages of RPL expressions can be easily shared. A curated, maintained library of patterns is surely better than using discussion sites like Stack Overflow as a regex repository.

When a pattern has been developed, tested, and debugged, it can be easily used in production. From a language with a Rosie library binding, like Python, Rosie is used in the same way that a regex library is used, with one key difference: in your program, you can tell the Rosie engine to import a package of patterns (from disk), after which you can use them by name.

While patterns can certainly be hard-coded into programs as strings to be compiled by Rosie on the fly, using patterns in programs by their names gives better run-time guarantees, due to ahead of time compilation, linting, and testing.

Pattern maintenance is facilitated by the readable, diff-able syntax of RPL, and by the use of unit tests for regression.

Finally, we are working now on building first class ahead-of-time compilation, in which compiled patterns are saved to disk for re-use. This allows us to separate the Rosie run-time (where matching is done) from the compiler, REPL, and CLI code. In a working prototype, the run-time library is around 50KB in size, statically linked.

Rosie is reasonably fast, at least when compared to Grok, even though we have made very few optimizations in its implementation. Rosie has a potentially very small run-time footprint as well, pending completion of our current development effort.

We welcome feedback and contributions. Please open issues (or merge requests) on GitLab, or get in touch by email.

Edit August 15, 2023: You can find my contact information, including Mastodon and LinkedIn coordinates, on my personal blog. The mailing list https://groups.io/g/rosiepattern has fallen out of use since we mostly use Slack, but perhaps it will be revived.